The TRUTH about “negative” numbers on finite elliptic curves!!

I think people often struggle to make cryptography concepts clear. I’m not claiming I can, but I can make a commitment to trying—starting with a click-bait title! I might get some information wrong since I’m not a cryptographer, but hopefully I won’t ;)

Prerequisite knowledge

The only requirements are algebra and modular arithmetic.

Elliptic curves

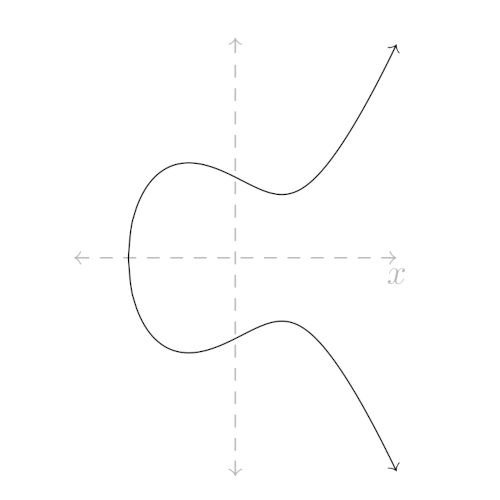

Elliptic curves are what we call functions of the form y² = x³ + ax + b. These functions can be written in different ways, but the representation I’m using is in “Weierstrass” form. The curve used for Bitcoin-related things, secp256k1, looks like this in Weierstrass form:

y² = x³ + 7

And if we graph it, it looks like someone punched a vertical line from the right:

It has a nice shape to it though—like the Snapchat logo turned on its side:

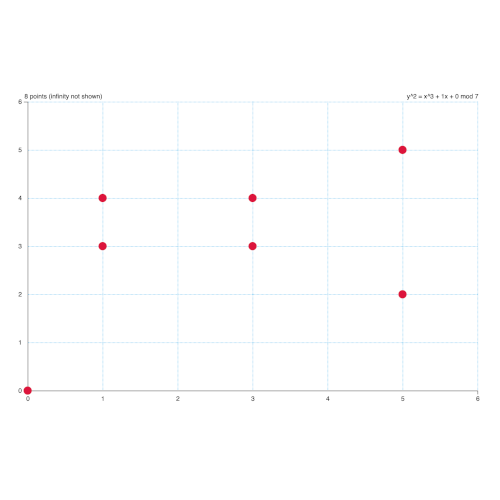

Elliptic curves on finite fields

Well, it was too nice for cryptographers, so they had to make the x & y values wrap around with a modulus! For secp256k1, this modulus is prime. I’d like to say it’s chosen to be prime because it sounds cool (since mathematically you can now say the underlying field form A GROUP OF PRIME ORDER!!!), but there are reasons for the selection that I won’t get into here.

Anyway, this is what it looks like with a modulus applied:

With a modulus, we’re able to wrangle an infinite number of points into something finite and countable. And since mathematicians love to count things, as I’ve learned through the math classes I struggled through years ago, we know how many points are in a modded elliptic curve as well. Let’s label the modulus applied to the coordinates of elliptic curve points “p”, and the number of points this function can generate “n”. In secp256k1, n is slightly less than p.

One REALLY important thing I need to cover before moving forward is that for cryptographic applications, we always mod the numbers we pass into finite field elliptic curve functions. You might be thinking “obviously! you told us they’d be modded by p,” but we actually don’t use p as the modulus for scalar inputs to our function. We use n! “Inputs” here refers to the scalar multipliers we use in elliptic curve operations, not the resulting point coordinates. I just had to mention that to avoid confusion moving forward.

Elliptic curve point operations

There are also operations we can perform on points, like adding one point to another, but the algorithm to do that is non-obvious and the details are somewhat irrelevant here. It is important to know it can be done in this special world of elliptic curves.

Why do we mod scalars by ‘n’ instead of ‘p’??

After n, the scalar multipliers we input start to produce the same points again since mathematicians proved we can’t have any more than n unique points on the curve! Well, why not just work with scalars mod p instead? Because the scalar multiplication operation has a period of n, not p—meaning after n steps, we return to our starting point.

I’ll also mention that after modding the scalar by n, all coordinate calculations are done mod p. Remember, n is the order of the curve (number of points), while p is the field size for coordinates.

The curious case of negative numbers

Coming back to the title, the TRUTH about negative numbers in finite elliptic curves is that they don’t exist in the traditional sense! When I talk about ‘numbers’ here, I’m referring to what cryptographers call scalars—the multipliers used in elliptic curve operations. So not point coordinates.

For the elliptic curves we’re discussing, I mentioned scalars are mod n (the order of the curve), and they’re defined to be non-negative integers from 0 to n-1.

So where do negative numbers come from? Am I duping the readers by definition?? Well, yes and no. I’m using “negative” here to mean “the additive inverse”—the thing you add to get back to zero.

With the set of integers, every element has an additive inverse (i.e., 2 + (-2) = 0). With the set of integers modulo some number n, every number still has an additive inverse, but it’s just the number that, when added, gives you zero mod n (i.e., 6 + 1 ≡ 0 (mod 7)).

With elliptic curves we work with prime p as modulus, which also makes p odd. What does this have to do with anything? Well, I can say that an even number added to another even number will never equal our odd p!

We can then label even numbers as ‘positive’ and odd numbers as ‘negative’ since every element in this set of positive numbers has an inverse in the odd set of numbers. There will never be an inverse of an even number in the even set or vice-versa, making the inverses mutually exclusive. It’s this mutual exclusivity that lets us relabel these sets as ‘positive’ and ‘negative’. ‘Negative’ is therefore redefined in this context to mean a set of inverses to another set rather than the traditional concept of negative.